1. Introduction

Capitalist economic forces have pushed independent dance artists2 into the sole trader model. At almost every interface of the arts ecology – from festival programming to tax returns – independent artists are conceived as complete business units, capable of participating in a marketplace where goods and services are competitively traded for value, theoretically offering a promise of surplus for the artist. Of course, this assumption is deeply flawed and fails to account for both the lived realities of practising artists and the structural impediments that prevent such a model from working.

Responding to this incongruence, this chapter analyses the sole trader model in the broader context of working conditions for independent artists. Firstly, from a legal perspective, the chapter considers the two ways a dance artist may be paid to work in Australia (employee or independent contractor), noting the significant workplace protections unavailable to the latter. Secondly, the chapter locates the sole trader model within this employment law context, offering a basic explanation for why independent dance artists have, by default, been pushed into this category. Thirdly, using case studies of five dance artists’ lived experiences,3 this chapter identifies the theoretical, structural and practical problems of treating dance artists as sole traders.

At the outset, it is important to consider the intended audience. This chapter attempts to tell the story that we – independent dance artists – know. For an artist, the chapter might provide solidarity and confirmation that their own experience is not singular. For funders and presenters, the chapter might reveal some uncomfortable truths about the precariousness of artists’ livelihoods and those stakeholders’ complicity in the top-down pressures imposed on artists. For the general public, the chapter might serve as an educational tool to better understand how an independent artist makes (or doesn’t make) a living.

Lastly, it should be noted that this chapter does not seek to be comprehensive. It is neither an academic critique of the political economy in which the artist exists, nor a wide scale survey of exploitative labour practices as experienced by dance artists. Rather, it is a starting point for a discussion; a communalising of challenges faced by independent dance artists and an opportunity to question them.

2. Working as a dance artist

There are two ways a dance artist may be paid to work in Australia: as an employee or as an independent contractor. There are important legal differences between these two terms that directly determine the dance artist’s rights and liabilities. While a little dry, it is necessary to consider these categories to understand the workplace protections and benefits unavailable to a sole trader.

2.1. Employee

In the dance context, the term ‘employee’ has become synonymous with ‘company dancer’, as the employer is typically an incorporated entity, such as a dance company. The dance artist’s term of employment may be fixed (e.g. a 12-month position) or permanent, and may require the dance artist to work full-time, part-time or on a casual basis. An employee must follow the directions of their employer, has an expectation of ongoing work, bears no financial risk in the business, has income tax deducted by their employer and is entitled to paid leave.

The terms of employment should adhere to an industry award, which is a legal document approved by the Fair Work Commission that sets minimum pay rates and conditions of employment (hours of work, penalties, allowances, etc). The most relevant award for dance artists who perform in a live context is the Live Performance Award 2020 (and accompanying Pay Guide), which sets the minimum pay rates for studio hours, rehearsals, performances and penalties (e.g. Sunday performances).

Alternatively, an employed dance artist may be covered by an enterprise agreement. This is a different legal document, typically negotiated between an employer and a union on behalf of employees, that sets the pay rates and conditions of employment for that particular workplace. If approved by the Fair Work Commission, an enterprise agreement will apply to an employee instead of an award. In the dance industry, the Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance regularly negotiates enterprise agreements for employed dance artists at major dance companies (see, for example, the enterprise agreements for The Australian Ballet and Sydney Dance Company).

In exceptional cases, an employed dance artist may not be covered by an award or enterprise agreement. In this case, the terms of employment are entirely contained within the employment contract that the parties agree to. This allows for a lot of flexibility, but the terms cannot provide less than the national minimum wage and the National Employment Standards (i.e. the 10 minimum employment entitlements set out in the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth)).

2.2. Independent contractor

Unlike an employee, an independent contractor (or a freelancer or ‘independent artist’ in the dance context) is not tethered to one employer. Independent contractors are engaged to perform a specific job, bear the risk of making a profit or a loss as their own business entity, issue invoices under an Australian Business Number (ABN), pay their own tax, and are not entitled to paid leave. Independent contractors fall outside the national workplace relations system and are therefore not entitled to a minimum wage or other entitlements or protections enjoyed by employees.

Determining whether someone is an employee or an independent contractor is not always a straightforward task. It depends on several factors that must be assessed holistically, rather than relying on the use of labels such as ‘employee’ or ‘contractor’. That said, in the Australian dance context, save for a very small number of dance companies that engage dance artists as employees,4 the vast majority of dance artists are engaged to work as independent contractors and therefore denied basic workplace entitlements. This remains true for those dance artists who, because of their close association with a particular dance company, may call themselves ‘company dancers’ but are nevertheless engaged on a project-by-project basis.

Analysing the historical reasons for shifting away from employing dance artists in favour of contracting them falls outside the scope of this chapter. But the benefits to organisations that engage dance artists as independent contractors are worth noting. Dance artists can effectively be hired ‘on demand’ – engaged under a contract that is tailored to suit the needs of the organisation or particular project. The duration of engagement, pay rates and work conditions are often unilaterally determined by the hirer, leaving the dance artist to ‘take it or leave it’. The hiring organisation also avoids administrative and financial responsibilities like obtaining personal injury insurance and meeting withholding tax obligations.

In the dance context, many independent contractors operate as sole traders. While the two terms may be used interchangeably, the former is more accurately used in employment law as a counterpoint to ‘employee’. The term ‘sole trader’ is used in commerce and taxation contexts when discussing different business structures (e.g. sole trader, partnership, corporation, trust). For the purposes of this chapter, the relationship between the two terms can be summarised as follows: independent dance artists typically operate as sole traders who may be periodically engaged by various organisations as independent contractors (rather than employees) for specific projects.

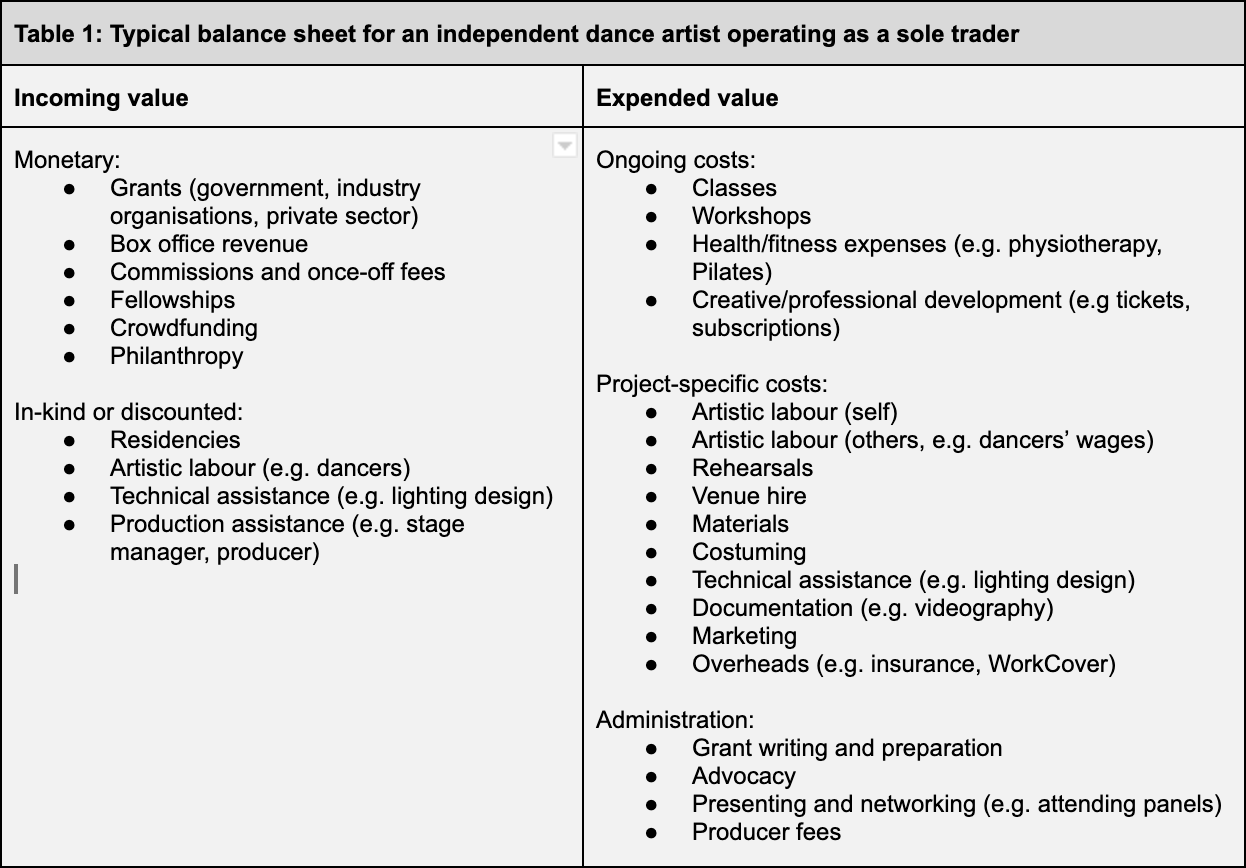

The next part of this chapter considers the practicalities of an independent dance artist operating as a sole trader, identifying the advantages and disadvantages of this model and proposing a typical balance sheet for such a business unit.

3. Dance artists as sole traders

A sole trader is someone who runs their own business. It is the simplest and cheapest type of business structure available, with minimal set up costs and ongoing regulatory compliance obligations. For independent dance artists, this usually involves obtaining an ABN and invoicing under that ABN and, if their annual GST turnover is $75,000 or more, registering for GST.

But a sole trader also bears the legal and financial risks of running the business. This means they have no guarantee of ongoing income, are personally responsible for any debts and losses, face unlimited liability if something goes wrong (i.e. their personal assets may be accessed to satisfy a debt or legal claim against them), and are liable to pay tax on all income derived under their ABN. Sole traders must also keep financial records for at least 5 years.

Like any sole trader, an independent dance artist must actively pursue income-generating activities, often from multiple different sources. Much of this income is sporadic, project-specific and only competitively available. While there is no meaningful data available on the success rate of grant and funding applications by independent dance artists,5 it is fair to say that, for most artists, the rate is extremely low and extremely unpredictable. For those projects that are funded, budgets typically only cover short periods of work and/or a small group of artists.

Conversely, an independent dance artist’s expenditure is substantial and constant. Ongoing maintenance costs, like daily class, are often too costly to access too regularly, and artists frequently work on their own or others’ projects for no or minimal fees. Running a project, like a show, involves many fixed costs that are typically unmanageable without substantial funding or the prospect of a healthy box office revenue. The expenditure column also includes countless activities that, although crucial to the artist’s sole tradership, are unquantifiable or, more accurately, not recognised as compensable by the market. These administration costs form such a large part of the artist’s business that the balance sheet inevitably ends in the red.

At the risk of over-generalising, Table 1 below attempts to capture some of the sources of income and expenditure for an independent dance artist operating as a sole trader.

For the same reasons that dance artists are engaged as independent contractors rather than employees, independent dance artists have, by default, been forced into the sole trader business model. An independent business unit with a profit and loss statement in the black is an appealing prospect on paper, and enables institutions to shift their financial liabilities onto the artist. This mode of engagement has become the default for all key stakeholders: government arts departments, the ATO, funders, presenters, hirers, and so on. Underpinning this engagement is an assumption that the dance artist is capable of being a self-sufficient business unit; of participating in a capitalist marketplace where goods and services are competitively traded for value, theoretically resulting in surplus for the dance artist. This belief is deeply flawed.

The next part of this chapter interrogates the assumptions on which the sole trader model is premised – the ability to trade, the recognition of value, the power to bargain and the generation of income. Underscored by case studies of five different artists’ experiences, the sole trader business model provides few advantages for the independent dance artist, while exposing them to financial risk and exploitative labour practices.

4. Critique of the sole trader model

4.1. ‘Trading’ as a dance artist

Treating dance as a tradable commodity is problematic because many aspects of a dance practice cannot be monetarily quantified, lack value in the marketplace and thus go unrewarded. Save for performance outcomes that attract box office revenue, very few elements of a dance artist’s practice result in merchantable goods or services. Vertical exchanges between dance artists and funders or presenters are largely defined by the balance sheet and maximising the ‘value’ of the artist’s work. There is little appetite on the part of these funders (and the constituents they represent, namely the public) for the other value a dance artist trades in; value that escapes the language of capitalism. Creative thinking and imagining, passing physical knowledge from one body to another, embodied research, artistic provocations and interrogations, and so on. None of these activities, some of which are more important to a dance artist’s practice than performance outcomes, translate into a balance sheet and are therefore omitted.

For those aspects of a dance artist’s practice that can be itemised, the true value of the activities is seldom understood by all market participants or, worse, is understood but ignored. From project to project, funder to funder, there is no consistency in recognising or rewarding artistic practice. Rather, there is a selective approach to ascribing value (e.g. the studio hire fee should be paid with money, but the dancer’s labour doesn’t need to be). This is heightened in partly or under-funded projects where the exchange of some money is believed to legitimise the whole project and thus permit the payment of some parts of the artist’s practice, but not all. As a result, many of the goods and services dance artists trade in must be traded ‘in-kind’ or below market value. As identified in Table 1 above, a dance artist will frequently rely on in-kind contributions from their peers and professional connections (e.g. working on another’s project without payment or asking a composer to create a sound design for free), and typically reciprocate by supplying their own discounted or free labour to others.

Case Study A: “Last year, I put together an application for funding from the Australia Council. It was for a paid development of a collaborative project involving a musician, filmmaker and me as the choreographer. I prepared the budget and asked an established artist to review a draft version. He had received AusCo funding many times before and was a regular peer assessor of funding applications. In giving us feedback on our budget, he wanted to know where our in-kind contributions were. He said our application wouldn’t be competitive – in the eyes of AusCo or the peer assessors – if we didn’t include substantial in-kind contributions, even if that meant including additional unpaid hours of our own labour. While his feedback wasn’t surprising, I was taken by the matter-of-factness of his advice; how certain he was that some things in our project had to go unrewarded.”

4.2. The (off) balance sheet

As Case Study A demonstrates, the off-the-balance sheet approach to making dance happen doesn’t just exist between dance artists. For a project to be supported, funders also expect (and need) in-kind contributions from multiple sources, not just the artist(s) involved. Venue hire, design costs, production assistance and so on, are all expected to be sourced for free or heavily discounted rates. Larger scale projects must also find an entirely separate funding body to co-finance the project, lest one funder bear all the risk. The result is a balance sheet where the income column total does not cover the outlays. Even if a single project is ‘adequately’ funded (that is, ignoring the significant in-kind contributions that go unremunerated), there is no income to cover all the costs that arise before and after the project: the daily classes, the costs of staying performance-ready, the labour of writing endless grant applications, and the daily administration of running ‘the business’.

Creating dance ‘products’ using below-cost labour and materials also creates a dual economy. Take the example of producing goods offshore: because labour is cheaper, the seller is able to enter the local market at a competitive price point while avoiding the expense of local production. For manufacturers, it’s a race to the bottom where an increasingly efficient market rewards maximal output for minimal input. In dance, this shadow economy is all too familiar, defined by its currency of personal favours and ‘good opportunities’. In an increasingly underfunded arts economy, the desire to get more-for-less forces the artist to shift the true cost of labour off the balance sheet and into the ghost budget. Self-discounting artistic labour is a semi-official prerequisite to being funded, leaving the dance artist exploitable by funders and presenters who reap the rewards of below-cost production. As Case Studies B and C demonstrate, presenters can deliver big products for audiences and government funders, but only if the artists are willing to work partly, or sometimes entirely, for free.

Case Study B: “I performed in a show at Dance Massive in 2019 that was produced and funded by one of the festival’s presenting ‘houses’. I was paid a lump fee of $960 and told it covered 40 hours of work. Just going by hours, that’s a pay rate of $24 per hour – well below the Live Performance Award rate ($30.05 per hour for that financial year) and ignoring the higher industry rates for dress/tech rehearsals ($40.20 per hour) and performances ($190.74 per performance). In fact, the producer’s budget for each dancer was so low (and detached from the industry award rates), that my lump sum fee actually only covered the three shows and half the tech/dress rehearsal time. In other words, the producer could not afford to present the show at industry rates, let alone pay for any pre-production rehearsal time.

The choreographer, who had unsuccessfully attempted to secure additional funding on their own, ended up using their personal savings to supplement each dancer’s income. This money covered less than half the rehearsal time, and we were asked to volunteer the rest. I consented: it was a good opportunity and I empathised with the choreographer’s impossible dilemma – present a show in Australia’s biggest contemporary dance festival without properly paying the dancers or present no show at all. Throughout the whole transaction, the producer seemed to turn a blind eye to the free labour – aware they hadn’t paid enough for the work to be presented, but expecting a festival-ready show nonetheless.”

Case Study C: “I had been working with a choreographer on a periodic basis over a couple of months in early 2019. I was invited to join the existing cast of the choreographer’s upcoming show in Dance Massive, which was being produced by one of the festival’s consortium presenters. I was explicitly told by the choreographer on two separate occasions that ‘there is no money in it’ and that the show was unfunded. I agreed to work for free. I felt like it was a valuable learning and performance opportunity, despite being unpaid.

During a tech rehearsal, I discovered the show was in fact funded and six dancers in the cast were being paid. I was not. And neither were two other dancers. Not only was my labour apparently not worth compensating, but I was also denied other employment benefits enjoyed by the paid dancers, like superannuation and WorkCover protection. (Even if my dancing was considered less valuable, was my risk of injury less worthy of insuring?)

While paying only half the cast was probably the choreographer’s idea, the producer was complicit in the whole transaction, choosing to ignore the fact they were presenting a show with nine dancers for the price of six.

Months later, the show was nominated for two Green Room Awards, which I found equally amusing and offensive because nominated shows must offer artists ‘industry award payment’ or a ‘profit share arrangement’. For the ensemble award, the names of the unpaid dancers were originally omitted from the billing and only added after we made multiple requests to be included. The choreographer ended up winning the second award – a major trophy won, in part, using my free labour.”

4.3. Unequal bargaining power

A competitive marketplace requires a minimum level of bargaining power to be held by each party to the transaction. The reality for dance artists is that almost every exchange is characterised by a gross imbalance of power; where the dance artist is someone needing ‘help’ to make their art. By positioning the dance artist as someone who lacks, funders and presenters are able to unilaterally define the terms on which the dance artist is engaged. (Indeed, hiring dance artists as independent contractors rather than employees, as discussed at the outset of this chapter, obviates the need for any minimum wage or working conditions.) Furthermore, without a shared understanding of an artist’s true value and cost of labour, funders and presenters are able to offer pseudo-rewards instead of, or as a supplement to, money.

The most egregious non-financial compensation is the promise of a ‘good opportunity’. Dance artists, like many artists, are constantly weighing up the financial benefits of a project or transaction against the non-financial value. Presenters and funders have long known this and leveraged it to their advantage. Not only is this bargaining chip absurd (and one that wouldn’t work in almost any other industry), but it hides a more sinister objective. The intentional non- or underpayment of an artist’s labour is not just about getting something for free. It is the wholesale devaluing and open theft of the very thing that defines the artist; the practice that gives their life meaning and purpose. Exploiting the significance of art to the artist is a violence; a calculated abuse of market power. With their back against the wall, the artist must say ‘yes’ to the opportunity because they have to. To say ‘no’ would be, at best, a ridiculous hope that there is a better (read: paid) offer around the corner and, at worst, a denial of self-actualisation. As Case Study D demonstrates, the more unequal the bargaining power, the more likely the dance artist is to be exploited. And it doesn’t just come from dance-illiterate hirers; arts organisations are equally ready, if not better equipped, to extract as much value from the artist as possible.

Case Study D: “There were ten students from our Victorian College of the Arts first-year group chosen to take part in remounting and performing Gertrud Bodenweiser’s Demon Machine in 2017 for the National Gallery of Victoria. Five of us went through to the performances; the other five were understudies during the early stages of rehearsal. The whole process lasted five weeks with around 27 hours of studio rehearsals, a dress rehearsal, a preview and four performances spread over weekdays, during and after university hours, and weekends. There were also times we were expected to travel offsite to get costumes fitted.

Coming into the project, we were told that, although it was funded through a Melbourne University Engagement grant and the ‘partnership of the University and NGV’, we would not be financially compensated. There were a few mentions that the cost of our costuming was in the triple digits for each person, which came as a shock considering at this stage we still were not being compensated for our efforts. This was definitely a bit of a wakeup call for me: realising that, because of our ‘inexperience’, our time and hard work was worth less than the attire we wore on our bodies.

In the end, we received around $300 compensation for our work on the project, mainly thanks to the insistence by the VCA Head of Dance that we be paid something, and the fact that we all signed a release form consenting to the filming (and future screening of) Demon Machine by NGV and Melbourne University.”

4.4. Finding money elsewhere

The sole trader model only works if there is a reasonable opportunity for the dance artist to actually trade; that is, exchange goods and services for value. Without proper reward of all artistic value and labour, the model fails. Out of necessity, the dance artist must look elsewhere to supplement their income work with non-dance work. For some, this work is in a related field (teaching dance, somatic practices, yoga, Pilates, etc), but for many, especially emerging artists, the work is in an unrelated industry, such as hospitality or retail.

Needing non-dance income to make the sole trader model succeed is paradoxical. Diverting time and labour away from an artistic practice for the sake of an unrelated job is counterproductive, and actually inhibits the possibility of becoming a self-sufficient sole trader. Less time spent on dance makes it harder to advance one’s skills and craft, thereby stunting artistic growth and, in capitalist terms, potential value in the marketplace. The discipline as a whole also suffers, populated with part-time artists who are unable to dedicate enough time and labour to realising their full potential.

Case Study E: “In my first year out of tertiary dance education I responded to a Facebook callout addressed to dance ‘students’ regarding a role in a film clip for a fashion brand. I won the gig and was told from the beginning that I would not be paid for the role, but that I would receive a voucher to purchase clothes from the fashion brand as a way of saying thank you. Happy to be offered a dance opportunity, I accepted.

Together with another dancer (who was also no longer a student), I committed to a handful of rehearsals, a fitting, and a very long day of shooting the film. I cancelled numerous work-shifts in order to be available. I accept that these were my decisions, and at the beginning I didn’t feel there was anything unfair about the process. I knew this was a ‘love project’ for the director and was under the impression that she was pulling together favours in every aspect of the project.

On the day of the shoot, I realised there were many other people on set being paid for their work: a film crew, a make-up artist, people styling the set and arranging flowers. I do not know if the venue we were in was being hired but, if so, it would have been expensive. It was during the shoot that I realised how much that changed things for me. My co-dancer and I were donating our efforts – our bodies, our selves – as the content of the film. And yet we were surrounded by people being paid a living wage.

Once filming ended, I learnt that the choreographer, a mid-career dance practitioner, had also been ‘paid’ with a clothing voucher, and only because she had insisted that some kind of compensation be provided to her and the dancers. I know the director was not a dancer, and this probably meant she misjudged what support we needed to create, rehearse and execute the choreography. But the make-up artist or the cinematographer wouldn’t have been offered a voucher as payment, so why were we? Why was it the choreographer and not the director who pushed for a voucher as an acknowledgement of our efforts? Would this situation have been more ethical if we were still students? I don’t think so.

These feelings stuck with me after the 12-hour shoot finished; while I worked my hospitality job that night until 2am, and into the next day at my 9-hour retail shift. Saying no to this paid work didn’t feel like an option. I needed money and to maintain rapport with my employers who were understanding of my changing availability. It’s experiences like these – which sadly still outnumber my fairly paid dance contracts – that leave me feeling more valued for my ‘day jobs’ than for the area of expertise I have dedicated my life to.”

How much non-dance income is sought or earned by an independent artist varies from person to person. Some may have lucrative or many ‘second jobs’, preferring to work in an industry that offers rewards commensurate with their labour. But, perversely, there are major structural impediments that operate to lower the overall earning potential of artists by disincentivising supplementary incomes. Under Australian taxation laws, a performing artist who records a loss under their sole trader ABN for a financial year cannot offset those losses against their personal income from other work if that annual income exceeds $40,000. This essentially means that a dance artist who supplements their income with non-dance work suffers a tax penalty unless they choose to earn well below the average Australian income ($49,805 per annum in FY18). The policy justification for this rule, according to the ATO, is to prevent individuals from reducing their income tax liability for ‘a business that is little more than a hobby or lifestyle choice’. Dance, it seems, is demoted to such a lowly status. The effect is to make it harder for independent artists to earn their way out of the low-income bracket or, more critically, make the sole trader model viable.

5. Conclusion

In the same financial year the five dancers in Case Study D were engaged to remount Demon Machine, the NGV recorded a profit of $26 million, adding to their overall worth of $3.95 billion. The other sponsoring organisation, the University of Melbourne, raked in $88 million profit, increasing its overall worth to $5.96 billion. Neither institution was willing to pay the dancers and, only when hassled, did they begrudgingly part ways with a measly total of $1,500. The dancer in Case Study D described the situation as ‘shocking’. Theft often is.

While not all exploitation is so obvious, Case Studies B and C reveal similar practices in the non- and underpayment of artists during Dance Massive 2019. The Australia Council for the Arts – the major funder of the festival – ‘expects that artists professionally employed or engaged on Australia Council-funded activities be remunerated for their work…Where an industry standard clearly applies, applicants are expected to meet those rates of pay’. Creative Victoria – the festival’s other major funder – has similar policies. That the producers in Case Studies B and C were able to obtain and later acquit their grants by paying below-industry rates, or no fees at all, not only demonstrates an abuse of the rules but a total lack of enforcement, either by the producers themselves or the funding bodies. Indeed, the expectation of in-kind contributions in grant applications, as highlighted by Case Study A, suggests any protocol developed by funders for properly remunerating artists is tokenistic.

Of course, dance is not an industry flush with cash. While there may be great inequality between major dance companies and independent artists, the true financial pressures originate from a societal undervaluing of the arts and an absence of government support. This ‘lack’ and the harm that accompanies it, is merely passed from one entity to another or, more accurately, pushed downwards to the sole trader. While every player in the industry may be a victim of an ever-shrinking pool of funding, the independent dance artist is relegated to the back of the queue – a dynamic that every player higher up the chain knows or wilfully ignores. The artist is denied power in the marketplace, kept at arm’s length with the promise of a good opportunity or, like the dancer in Case Study E, charity in the form of clothing. Keeping the independent dance artist in a position of need reinforces the perception they lack compensable value.

So, what conclusions can be drawn? While neither an academic nor empirical study of the sole trader model, this chapter can offer three general observations:

- the sole trader model is inappropriate for independent dance artists because it is premised on a series of commercial assumptions that do not exist in the dance context (namely, proper recognition of the dance artist’s value, the ability to competitively trade and bargain, and the ability to generate income from dance-only work);

- the sole trader model is designed to benefit funders, presenters and hirers who can tailor the engagement of dance artists to suit their needs, while avoiding the financial liabilities and true costs of supplying the art; and

- based on the case studies, which are necessarily selective but indicative of common experiences, principled messaging about rewarding an artist’s labour with industry rates is not followed in practice nor enforced, resulting in labour practices that exploit the weakest player in the market – the independent artist.

This chapter has identified several structural and practical problems with using the sole trader model as the primary mode of ‘doing business’. While capitalist economic forces continue, so too will the risks of exploitation faced by independent dance artists. This chapter should serve as a starting point for a conversation about this topic; an opportunity to identify where the harm is arising and where change can occur.

As a final point, some consideration should be given to how these structural problems can be redressed. The evidence used in this chapter is not comprehensive and mostly anecdotal, largely because there is no significant data available that specifically considers the financial pressures and labour practices experienced by independent dance artists in Australia. While adjacent data for performing artists generally is available, no in-depth and widespread discipline-specific survey for dance has been undertaken. This gap needs to be urgently addressed. Attributing quantitative data to an under-represented group of artists would not only make those artists visible to funders, government and industry organisations, but also equip them with the language needed to speak to those stakeholders. Determining what that survey should look like and how it should be executed is the logical next step. If successful, such an inquiry could shift the way independent dance artists are viewed by stakeholders and open the door to different ways of working and creating.

1 Rhys Ryan is a lawyer, legal academic and independent dance artist based in Melbourne.

2 In this chapter, unless otherwise specified, the term ‘dance artist’ is used in its broadest sense to include dancers, choreographers and artists whose practice primarily involves the discipline of dance.

3 The artists’ stories contained in the five case studies have been edited for brevity and clarity but otherwise remain the words of the contributing authors.

4 See, for example, The Australian Ballet, Bangarra Dance Theatre, Sydney Dance Company, Queensland Ballet and WA Ballet.

5 Grants In Australia 2018, published by Our Community (owner of SmartyGrants), identified grant trends across all sectors in that year, not just arts, and reported a 66% success rate. Data was collected from a pool of 2,012 respondents, of which only approximately 13% were seeking arts and culture grants. The survey included organisations of all sizes (including those with an annual revenue exceeding $1 million) and did not separately identify grants sought by individuals.