Perspectives on professions.

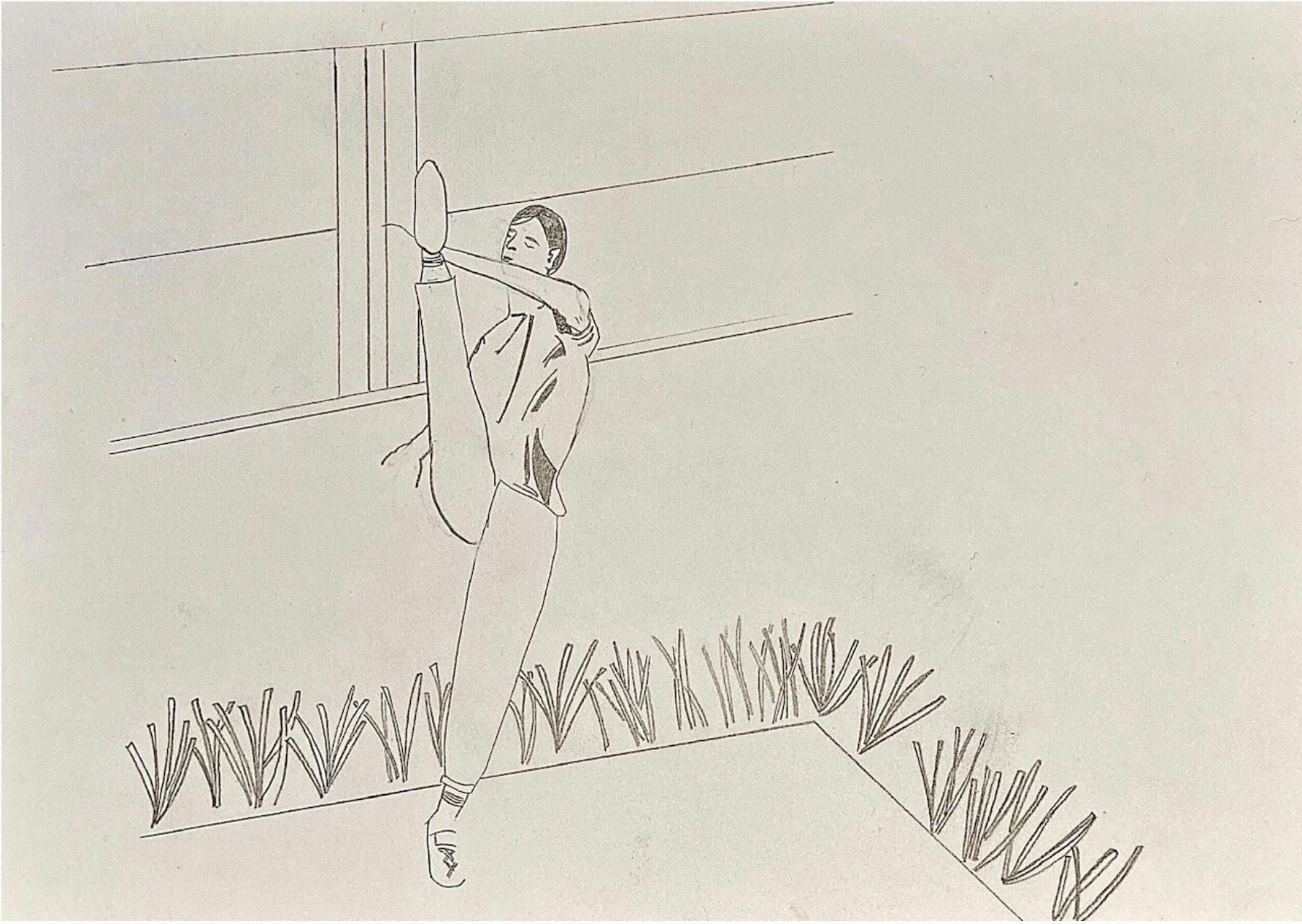

What If I Did Something Else is a comparison of my life as an independent artist compared to Michael Firrito as an ex professional North Melbourne AFL player.

I am interested in highlighting perspectives from different professions and lifestyles and comparing it to my own. I am an independent artist practicing in the field of contemporary dance. As part of this comparison, I have interviewed Michael Firrito, who played for North Melbourne in the AFL between 2002-2014. Certain aspects of the conversation act as an instigator for personal ‘train of thought’ which I have documented in bold underneath it’s quotation to gain further insight into how our lifestyles and career pathways may vary or align. William McBride, Melbourne based independent artist, has written comments in italics as the editor which I have decided to include in this piece.

With the approval of Michael, the quotations from the interview have been appropriately summarised and paraphrased for the purposes of this piece. This is not a direct transcription of our conversation.

The interview with Michael took place on Tuesday the 7th of July 2020.

Interview began at 11:00.

Ben Hurley: “To start things off, when did you start playing football and did you always aspire to play in the AFL?”

Michael Firrito: “Ever since I was little I always knew I wanted to be a professional footballer. My journey was always related to my family. I have two older brothers and an older sister; ever since I could walk I wanted to do what my siblings did.”

B: “How old were you when you knew that you wanted to be a professional football player?”

M: “Growing up I was a Collingwood supporter and one of my earliest memories was watching them win the premiership in 1990. After the game I went out to kick the footy and I suppose this is when my obsession with the sport began. Ever since I was 6 or 7 I always had a footy in my hand.”

B: “Right, then it must have been a huge sense of accomplishment when you were drafted for the AFL league I imagine?”

M: “It was really exciting. I was a committed and strong junior. My draft year I wasn’t actually drafted so I had a bit of an interrupted year. I missed out on two drafts that year; the main draft and the rookie draft. But then the following year I went to Hawthorns Reserves and spent a year playing there and then was rookie listed after that. It was not your traditional young talent pathway where you get drafted straight away.”

B: “Not being drafted initially must have been challenging in so many ways. So what’s the drafting process like? Do people come and watch you throughout the year or is it more of a like 1 day trial type of thing?”

M: “Yeah, there are scouts that come and watch you throughout the year. There are also talent days where they test your endurance, speed and strength alongside doing player interviews. I knew there were clubs interested; I had spoken to half a dozen clubs before the draft and was eventually picked up by North Melbourne.”

As an independent artist, auditions / application processes take up an immense amount of time, effort and unpaid labour. They are incredibly time consuming, anxiety inducing and usually result in rejection / no outcome. There are many deeply thought out and passionate projects that currently only exist in theory, as they have never had a chance to materialise. For the small to medium arts sector, projects take years to develop and present; there tends to be a lack of continuity for projects being funded throughout the span of its lifetime adequately, particularly in Australia. One project will need several successful rounds of applications which can take years, staggering any type of creative process.

B: “How did you feel when you weren't drafted your initial year?”

M: “It was hard. I had a goal in mind and I knew what I wanted to do. You turn 18 and you're doing your VCE; everything comes at once. At the same time I think it was also really good for me. Players that tend to get drafted straight away don’t make an impact straight away. They’re normally on reserves for 2-3 years anyway, so it didn’t really affect my development. In fact, it probably made me mentally stronger and more resilient.”

When Michael was successful in getting drafted by North Melbourne, he had a great sense of security and stability; being successful during the drafting process only happened once throughout his career. As an independent artist, success and failure is a constant throughout one's entire career; through writing grants, involvement in projects, auditions. Although failure can be depressing at the best of times, it has also assisted my development and growth through forcing someone out of their habits and desirable rhythm.

B: “Did many of your friends get drafted when they were 18?”

M: “Yea there were quite a few that got drafted including James Martell who went on to win a Brownlow Medal, Luke Hodge, Garry Ablett Jr., Sam Mitchell and a few others. That was the one that I missed out on but then the following year I got drafted. I also played juniors with Sam Mitchell, who also won a Brownlow medal. He was a huge mentor to me during this time because he also didn’t initially get drafted. I knew people had done it before, which gave me confidence.”

B: “How did it feel playing with players who were originally your teammates to then go up against them in the AFL?”

M: “It’s a pretty small industry so you get to know everyone. Football is so competitive and so aggressive which is quite confronting at times. One second your mates and then you're on the field competing against each other for two hours.”

B: “..And I guess there is just so much at stake when you’re playing AFL; there is a lot of weight on your shoulders to not only hold yourself but to also hold the team and all the supporters watching you.”

M: “Yeah there is a lot of pressure and even more so now with social media and Fox Footy. Every game is televised and there are 20 shows where they talk about everyone and everything.”

Competition has played a major role in my lifestyle and within the Australian culture as I know it. As a young kid, my parents put me in an array of sporting activities (‘as every young Aussie boy should be’). All of this bred a type of competitiveness that focuses on an ideal of winning - no matter what it takes. It creates a tension that humans learn to crave.

As a choreographer and dancer, I have been trying to re-imagine these habits and learn how to invite a more playful competitiveness and focus on alternative methods of self development. I am curious about different types of competition and questioning the lines between what is innate compared to what is learnt.

B: “You are very scrutinised that’s for sure. And what was your relationship like with school?”

M: “It was full on. I grew up in Gembrook which is an hour out of the city. I would get picked up from school at 3:30 and would start training at 5:30; this would happen 4-5 nights a week. I wouldn’t get home until 9:30 so there wasn’t much time for school. Because of this, I didn’t do super well on my VCE; I got an ENTER of 54, which wasn’t terrible, but it also didn’t leave me with many options…”

“…My first year out of high school I was still thankful for my football. The Box Hill TAFE organised a Sports Management course for me because of their affiliation with the Hawks. I was drafted my second year of the TAFE course, so I deferred and never completed it.”

B: “Right, and during your career, what was your training and day to day life like? What did your general week look like during the on- and off-season?

M: “It’s full on. Off season is probably when I was training my hardest. Monday, Wednesday and Friday are full days; half days on Tuesday and Saturday; Thursday and Sunday would be typical days off. During my time playing AFL it was pretty much 24/7 though, even when I wasn’t at the club I was mentally preparing myself and watching my diet, etc. The contact hours are hard to say exactly as it varied so much from week to week and on/off-seasons.”

Although his schedule and contact hours weren’t the standard 9-5, Michael’s schedule still had consistency in the sense that it was split into 2 different seasons; ‘on’ (playing matches) and ‘off’ (training) seasons. I wonder what it would be like to have some sort of consistency as an independent artist. For me, each day, each month, each year feels so vastly different from the other. The only consistency that I have is in my hospitality job. I imagine what it would be like to have my year split into 2 different seasons, where one half I am rehearsing, training, in process, and the second half I am performing. Although I know this model would create various structural problems within the arts, there is something legitimising and stabilising about this way of working as it has direction and trajectory. It happens to a degree with programmed festivals such as Dance Massive, Melbourne Festival and Fringe Festival, but on a much smaller scale and over a longer/more drawn out period of time.

B: “You had a long career that lasted for 14 years, how did you find the transition between your earlier and later career? When do you feel like you were at your peak performance?”

M: “I definitely got better as I got older, I was more mature. Physically I wasn’t as capable but when I was younger I was a bit too intense; everything was so serious and I put a lot of pressure on myself. When I got older I was more relaxed and comfortable in what I was doing. I also had kids later in my career and so they took a front seat which made me more well rounded and helped me improve my game. I probably should have had them when I was younger.”

Will: This is a really interesting point in relation to some of the other sections, and other conversations about the difficulties around maintaining a career when you have kids especially for women/mothers. Paea Leach has been focusing on this topic. A really strong contrast to this framing that having kids helps to make the player more rounded.

This makes me think of the 3 umbrella terms known as ‘emerging’, ‘mid’ and established’, used to define the merit of an independent artist's career. I graduated from the VCA in 2016 and will supposedly sit in this emerging category for approximately 5 years, until I am 26, which was when Michael experienced himself finishing his most ‘physically capable’ years. Not very often, a recent graduate may land a job in a full-time dance company, allowing them to utilise their most ‘physically capable years’. Even though this rarely happens nowadays, it still feels like the most understood way of having a career as a dancer. Considering there is no full-time dance company in Melbourne, this way of working feels particularly far-fetched, even if we travel abroad. The independent artists ecosystem has shifted and adapted for a particular reason - an artist's career varies from person to person, there is no ‘one size fits all’ mentality. Being an artist inevitably encompasses adapting new models of working in relation to time and therefore there needs to be more ways of understanding the career trajectory of an artist, yet also being open to shifting the models to best suit each individual artist's practice.

A clear difference in these professions in relation to age is in the notion of one’s ‘career ending’. For a footballer, there is a clear ending to a players professional career (when they are out of contract), whereas for an independent artist it is not as distinguishable. An artist’s career varies significantly from person to person, and just because an artist is ‘out of contract’ (not earning monetary value directly through their artform) for x amount of time (or ever at all, which happens more regularly than one may realise) does not reflect their devotion to their artistic practice and contribution to the artform. Some of the most influential and well known established artists include Trisha Brown and Rosalind Crisp, both of whom have had 40+ years of choreographic and performance experience and were continuously/always working on their practice in a variety of ways, shapes and forms.

M: “I was known for being a pretty aggressive player, I think a lot of that came from the pressures that I put on myself. As I got older I was able to manage it much better. When you get older there is more expected from you, which gave me the experience to deal with it.”

B: “Did you find that you were more nervous at the beginning or at the end of your career?”

M: “If I broke my career into 3 sections, the middle was definitely the most difficult; it’s when I doubted myself the most. The first section I was fearless, I was young and nothing got in my way. The last third of my career I learnt to just enjoy it. I finished playing when I was 32, but from 27 onwards it was almost like my last year but I just kept going, which I wasn’t expecting.”

B: “Did you see many similarities between yourself and any new/young players joining the team?"

M: “I enjoyed working with younger players later on in my career because I could see myself in them. I guess it’s like any competitive profession; when a new kid gets drafted you start to question if he will take your spot. It’s really competitive even within the teams because there are only so many contracts. When I was younger this really affected me whereas when I was older I thought ‘well, if he's good enough to take my spot then that’s better for the team’.

Will: Interesting to think this kind of thinking in relation to dance/art making, being at the cutting edge, being skilled, attracting attention etc.

B: Hey will can you please elaborate on what you mean by this in relation to the quote?

W: I think I mean the anxiety that you can feel as an artist about wanting to be making ‘good work’; to be creating something new, or to be at the cutting edge of your craft, etc. Thinking about parallels, additionally, worrying that another dancer might be ‘better than you’ and take your role in the community.

B: “Do you feel like this internal type of competitiveness ever stopped your team from winning?”

M: “At the end of the day the most important thing is the team's success and in order for that to happen we need every player to be at the top of their game. It’s a bit of a paradox, because early on in your career you need yourself seen, which I guess could be seen as selfish - I don’t think it’s wrong, everyone is just trying to establish themselves. However, whilst you’re thinking about yourself, you’re also thinking about the team and the club. It’s better to have an off day and that the club wins than the other way around. I think that the competition side of things actually really helped me improve my game because I was always pushing myself.

B: “What was one of your proudest moments as a footballer?"

M: “I have a couple. Team success-wise includes making it to three preliminary finals. In 2014, we played Essendon and we were 30-40 points down, it was half-time and I was out of contract. We also hadn’t been in a final very much or in a while; we had never been in a grand final nor had we ever won one. We just came back and won against Essendon. It was at the MCG, it was a Friday night, there were 80,0000 people watching. I remember thinking ‘shit we are in a lot of trouble here’. We stormed home and won; the feeling after the game was incredible. I remember getting home; it was late and Foxtel were playing highlights of the game, I was almost getting emotional watching it because of how much it meant to me.”

“Also milestone games where I got to carry my little boy out onto the grounds with me was pretty special. He was only three and won’t remember any of it, so luckily there are photos and videos through social media for the memorabilia.”

Will: Interesting literalness of pressure… Almost* got emotional :-).

B: “Earlier in the conversation you mentioned a few injuries throughout your career, can you elaborate on this?”

M: “I had two injuries; one that caused my knee to continue filling with fluid, and a torn quad. These injuries affected everything, really, but mainly my power and kicking. I’m not the most talented player so I relied on my power because I’m a physical one-on-one player, so I was like ‘well what do I do now? I don’t really have many tricks’. To combat these injuries I had physio and pilates sessions. I also had orthokine treatments to help regenerate cartilage, which really assisted my recovery. If I was playing in the 80’s though, I would have been done. Overall, I was pretty lucky compared to some other players.”

B: “What type of access did you have to treatment?

M: “When I started in the year 2000 we had two part-time physios that were there for two-three hours, three times a week. However if you needed a physio outside of that time you needed to book an appointment at a clinic in the city.

… Now there’s four full-time physios and a full-time doctor at the club all the time. There’s so much support; you have so many people there to make you the best player that you can be. I had a physio pretty much everyday who also helped me with my strengthening and conditioning work; I was really lucky, I had a lot of help. All of that was at no extra cost. You know you’re lucky and fortunate however you’re just so used to being in that bubble so you get used to it, it’s hard not to take advantage of it.”

As an independent artist there is no support similar to this. All Physio and Doctor appointments, unless on the rare occasion of being contracted with a company, have to be self organised and covered. There is always that consistent battle with myself of ‘should I get treated’ vs ‘can I afford to get treated’. I have recently been diagnosed with 3 bulged discs in my lower back that I continued ignoring; it took COVID-19 lockdown periods and government support money to finally get professional guidance and assistance.

B: “So, during your career, how were you contracted?”

M: “It varies from player to player; but the longest contract I had was for three years. I also had two two-year contracts and the rest were one-year. Contracts are always a bit of a balancing act - if you see it from the club’s point of view and they have an injured or older player, they need security too. In that regard, clubs definitely operate like a business. As much as I say I love the club, I came to realise that if I wasn’t performing they would get rid of me as quickly as they contracted me. You also see players now changing and shifting clubs more regularly, which supporters get riled up and think ‘How could he do that?!’, but every club and player has to do the best thing for themselves.”

As an independent artist, I am constantly working with a range of different artists/companies/choreographers/organisations. This can be viewed as a positive thing because the more people that someone works with the more knowledge/information they have, and therefore the more they can offer within a process. However, at the same time, it means that there are prolonged ‘dry spells’, where artists are in between contracts and needing to source other work. Ironically, with programmed festivals such as Dance Massive that happen once every two years, it crams a lot of work/opportunities into the same time frame, providing an overflow of work and often forcing professional artists to choose between different projects. I do love the agency and freedom in being able to forge my own career pathway, however, I wish there were more possibilities to work more consistent/full-time hours on a more regular basis, or that the work was spread more evenly throughout the year.

B: “Absolutely, everyone responds differently to different situations. And how would the club calculate your salary?”

M: “In AFL, there are two types of contracts - yearly and incentives. A yearly contract is say, $200K, whereas an incentives wage would be a base of $100K, and then you get paid X amount as a top-up depending on how you perform. I had a mix of them throughout my career; you generally start on an incentives, then move to a salary, then back to an incentives. Of course, everyone wants to be on a salary. When I started playing in 2002, my first contract was $17,500, so it’s come a long way. I still feel very lucky, I got paid handsomely to do what I love and ultimately something I would have done for nothing.”

This notion of ‘labour of love’ is something that comes up quite regularly for any dancer/choreographer/artist; “I love what I do so it’s ok to not get paid” or, “It’s good exposure and a good experience”. Although these are valid reasons to do a project and it’s reassuring to hear Michael say that he would have done the same thing for his footy because he loves it, however, this donation of time, efforts and expertise happens far too regularly in the arts, and it needs to change. In saying that, this ideology can enable really interesting moments to unfold as it fuels the art with passion and desire, rather than putting a monetary value on it. However, this needs to be more of an active choice made rather than something that happens by default.

There is something much more validating and affirming about getting paid properly/at all for a project; it can feel like I’m on the right track and my career is moving forwards. It also allows me to fully concentrate my energy into the project as I’m not distracted by other work or other sources of income, allowing the process to be digested and realised properly.

B: “How did you survive on $17,500 p/a?”

M: “Well, haha, yea... that year I had to live with Mum and Dad and would drive in everyday. There were 4 other boys who got drafted that same year, so we would all drive in together; we would spend about 3 hours in the car everyday. It was definitely harder, and my lifestyle has changed quite significantly since then.”

I can only speak for myself, however being paid $17,500 as an independent artist would be considered a reasonably good year, hence why having a side hospitality gig is a reality potentially forever unless deciding to join/landing a full-time job in a dance company. Although I saw myself following the full-time dance company pathway more seriously when I initially graduated from the VCA, I have also come to realise that, although it pays well and has great security, it is not something that particularly interests me anymore. This job title forces an artist to become one thing with a particular skill set, and extinguishes any sense of agency. So far, in my career even with many side gigs and many unpaid dancing opportunities, I have been able to work on my artistry across a range of different facets. I just wish I was appreciated/paid properly for this and for my place in society.

B: “How has that type of salary sustained you until now?”

M: “Don’t get me wrong, it’s great money but it’s definitely not enough to not work for the rest of your life. I’m not retired. It’s been hard actually, everyone that I went to school with their salary would start low and then increase, whereas mine was the opposite; it started really high and then decreased. I came out with a lot of money but it’s like, ‘Well I’m 32, so now what am I going to do?’ I was lucky to have a supportive family that aided me in spending my money wisely and on investments; you see a lot of players blow the cash. It’s definitely not like the NFL where they get paid massive; I think it’s around $1M p/a.

B: “Were you working when you were contracted with North Melbourne?”

M: “Yeah, during the end of my career I was doing three-hour placements per week at Colliers, a commercial real estate company, which is where I have transitioned to. I do enjoy this type of work but I still love football; before COVID happened I was back with North Melbourne as a development coach and training 15-19 year old kids at Hemisphere.”

B: “And finally, what do you feel like you miss the most about it?”

M: “Now, I probably miss the relationships more. I like football but I love coaching a player’s development. Although I received a lot of validation through being a professional footballer, it was also challenging at times; I have to watch what I was doing all the time and so it was hard to let my guard down. Overall, I am so thankful for my footy as it has opened up so many doors for me.”

Interview finished at 11:50.